Covid-19 seemingly came out of nowhere in early 2020 and proceeded to impact our lives – across the world – in so many ways. The pandemic brought lockdowns and ushered in new ways of working and brought societal change. How did it impact the global automotive industry?

Living with lower volumes and supply chain fragility

This has probably been the biggest impact. Companies have been forced to manage their activities in unprecedented ways as Covid-19 shut sales markets and shuttered factories. Many are still on the learning curve in terms of understanding how to manage unexpected disruptions, but at least more are aware of where the business risks lie and the consequences of inaction.

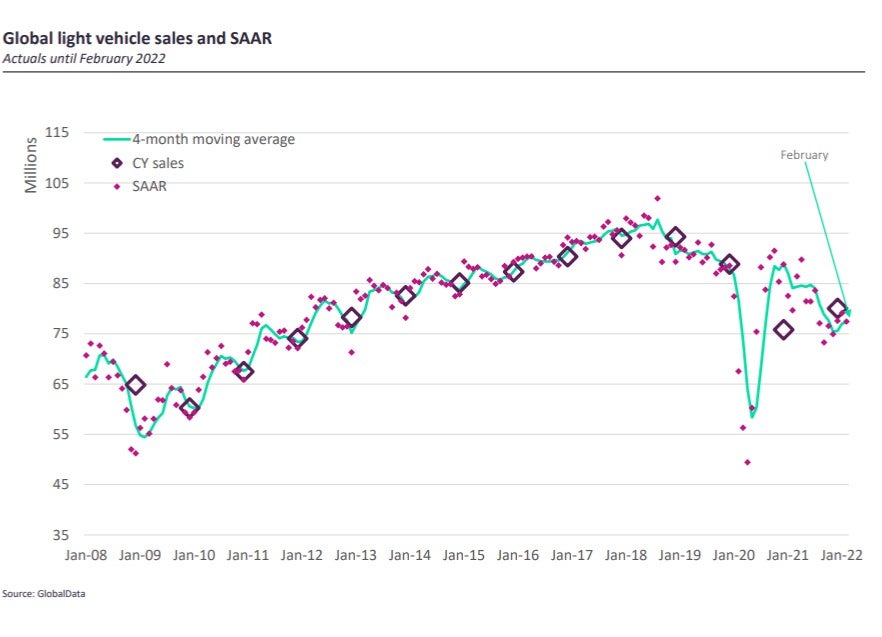

As the chart below illustrates, the global light vehicle market fell off a cliff in 2020. While there was market recovery, that recovery was uneven and blunted by supply chain problems (notably shortages of semiconductors) that constrained sales in 2021. The market remains well below pre-pandemic levels.

Population lockdowns in 2020 shuttered factories and dealerships across major markets. It started in China (Wuhan, Hubei). Shuttered components factories there quickly hit Korean vehicle manufacturing operations. Then companies in Europe were impacted with ripple effects from stalled parts output in Asia. Before long, the public health crisis spread to Europe, starting with Italy. Pretty soon Covid-19 (quite literally) went viral and was everywhere. An industry such as automotive with its complex, elongated supply chains (20,000 parts in a typical vehicle) and international sourcing patterns was always bound to be heavily exposed.

As Covid-19 infection rates surged, companies were faced with mandates to cease manufacturing operations and send workers home. Besides the immediate challenge of managing cash flow to pay workers when sales revenues were suddenly halted, there was a need also to understand how supply chains and factories worked. Besides suspending manufacturing activities for an unspecified period, there was also the knowledge that at some point – but no idea when – everything needed to be restarted again. Restarting factories was to prove challenging, too.

Undoubtedly there are lessons in cash management and strategic prioritization that will become pillars of many companies’ operational strategies for years to come. Early in the crisis, many companies reached for the oxygen provided by the opening of new credit lines. This buffer helped get companies over the hump of the first wave of the pandemic while later recovery in market levels, allied with a laser-like focus on costs and the bottom line, saw many players roar back to profitability in the second half of 2020.

Later in the year it was to be a generally chaotic picture with restarts as manufacturers struggled with the effects of ongoing disruption down the supply chain. The public health crisis itself was characterised by variances in responses – and indeed strategies – by national governments which meant that the volume of infections and associated economic disruptions varied considerably across the world. With long and complex supply chains spanning the globe, vehicle makers and major suppliers were caught out by both the fragility and a lack of transparency in their supply chains.

Commendably, many OEMs and major suppliers were able to repurpose their factories to make ventilators, PPE and other health equipment that was in high demand in health services.

Striving to better understand supply chains – alongside managing plants as flexibly as possible – has been given added urgency by the shortcomings shown up by the dramatic swings caused by Covid-19. Are the lessons being learnt and new solutions applied? That is harder to assess, but companies are making better use of process tools such as blockchain to manage their supply chains. Shortages of certain types of component and their costs will also have raised awareness of risk mitigation strategies inside procurement departments.

A big lesson is that the supply chain – in all its complexities – cannot be taken for granted. OEMs and suppliers need to undertake in-depth analysis of their supply chains, understand where bottlenecks are likely to occur and stratify their commodity purchases accordingly. This is what Toyota – the masters of lean production – did, in learning lessons from the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and others need to follow suit now. The cost of warehousing supplies of crucial components is minimal compared with the impact on production of supply chain breakages.

See also: Pressing issues for automotive supply chains

The CASE is altered

The CASE acronym that sums up four major auto industry megatrends – Connectivity, Autonomous, Sharing, Electric – has been around a while now. The letters sometimes get mixed up in other forms (ACES, for example). The relative speed and importance of the CASE constituents has been changed by the pandemic, though the shifts are subtle and overlay changes to relativities that were happening anyway. The ‘E’ is more important now than it was pre-pandemic. The last two years have seen an acceleration in the momentum towards electrification – in terms of both market trends and supply-side activities. Investment in new electric vehicles, the required technologies (such as new vehicle platforms) and component systems (powertrain/drivetrains, especially batteries) has taken off. The pandemic also gave way to talk among politicians of ‘green recoveries’ and building back better, with rethinks, or at least a change of emphasis, evident in the political discourse surrounding topics such as transport policy and sustainability.

In many ways, electrification has been given the jump-start it needed via the pandemic. Several factors are at play here. Market incentives to assist demand have been very prevalent in Europe, where the share of BEVs sold in the market leapt from 3.16% in Q4 2019 to 9.9% in the whole of 2021. When government support for the industry came after the worst of the 2020 decline, it was frequently packaged in green wrapping paper. Government sponsored incentives have coincided with a raft of new BEVs on the market as OEMs move to meet 2021’s EU CO2 emissions target and more stringent future regulations.

The long-term residual impacts of the pandemic have still to be determined, particularly with more working from home and less demand for public transport (usage is significantly under pre-pandemic levels in the UK) as numbers of weekday commuting journeys have declined.

Lockdown and the post-lockdown environment will likely lead to individuals and households reassessing their transport needs and solutions. Modal mix could change, but it’s not necessarily going to be to the detriment of private transport. If there is less appetite for shared mobility or public transport, those fortunate enough to have the means may well have added a BEV as a purchase option or possibility for future consideration, to their household.

Sharing (through ride-hail) has undoubtedly seen some disruption due to the pandemic. The big question is whether this is a long-term shift in people’s sensibilities or whether we get a return to pre-pandemic trends. There was some recovery to rider numbers and revenues in 2021, but the Omicron variant put a dampener on things in early 2022. We have also seen the ride-hail companies pivoting their business models towards goods and food delivery.

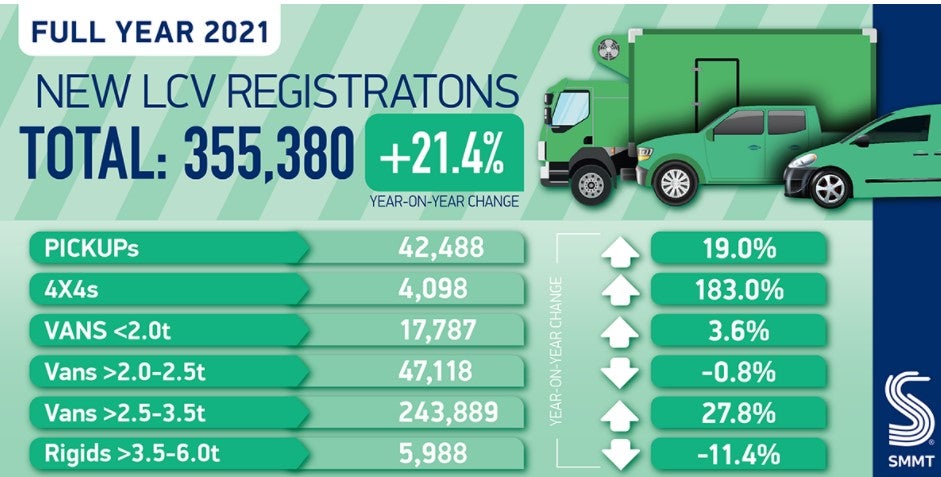

More online retail of goods and delivery to homes has been a major contributory factory in van demand remaining relatively buoyant as major delivery fleets have seen their business surge. Already growing online shopping was lifted further by lockdowns that curtailed physical shopping. The trend to more online shopping has stuck, even as physical shopping has returned.

UK new light commercial vehicle (LCV) registrations ended 2021 up 21.4% at 355,346 units, some 62,723 units more than in 2020 and just 2.8% down on pre-pandemic 2019 (365,778 units) – despite industry-wide semiconductor shortages which hit the market in the second half. Big fleet operators (such as Amazon) are also giving more consideration to electrified van fleets. Strongest growth last year was in the mainstay 3.5 tonne panel van segment, with 2021 sales up an astonishing 27.8% at 243,889 units. One supporting factor: vans are generally a little less advanced tech (and therefore electronics parts) intensive than passenger cars and overall volumes are lower, so they are a little more able to withstand the semiconductors shortage.

The jury is out on the ‘A’ in CASE: Autonomous. Autonomous Vehicle (AV) tech has been a big consumer of investment and R&D spend over the past five years. Besides the direct spend in R&D departments or JVs, there has also been plenty of M&A activity involving startups and tech specialists – both software and hardware. With question marks over sharing, the business case for autonomous loses some of its lustre. Much of the push for autonomous has been to see shared mobility businesses move to driverless, thus reducing fixed and variable costs and bringing the companies sustainable profitability to justify sky high stock valuations.

While ADAS systems will inevitably continue their progression, it seems doubtful presently that Level 4 and Level 5 autonomy will be seen at scale anytime soon outside of tightly policed geofenced areas.

Digitization of automotive retailing – at last

One area that has demonstrated more resilience than most is automotive retail. Since the internet’s inception, vehicle retail has looked ripe for digitization. However, for whatever reason it’s never really taken off. Sure, consumers use the net to research and evaluate their next purchases, but the customer journey never really evolved through the whole buying process. With many dealers forced to close their doors due to lockdowns, dealers and national sales companies were forced into a rapid re-evaluation to save their businesses. Never has necessity is the mother of all invention seemed more apposite.

Now, for automotive retail, it’s no longer a case of “clicks-to-bricks” but more a case of click and collect. Retailers are offering doorstep delivery of test drives and new vehicle purchases. Electronic signatures and credit checks are commonplace. In short, much of the friction has been taken out of the buying process. It’s easy to conceive that future showrooms will be just that. Places where people need to kick the tyres and can visit as part of their buying process. Everything else will be handled digitally, removing much pain from the buying process.

SUMMARY

How has the pandemic impacted the auto industry? In short, established practices and assumptions on how the industry operates have been severely challenged. In effect, there is a divide between the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic automotive worlds. While both of those worlds face the same underlying long-term megatrends, the business landscape has been irrevocably changed in many respects. Perhaps the biggest single change is in mindset and the new need to address, through strategies and agile event-reactive tactics, a world of much greater volatility and uncertainty.

Supply-side impacts and responses

- Population lockdowns across the world at different times highlighted the need for greater understanding of automotive manufacturing supply chains. Companies are grappling to develop risk mitigation strategies and embrace ‘what if’ scenario planning.

- Vehicle makers are generally working more closely with their Tier 1 suppliers on volume/order changes and identifying break points further down their supply chains.

- Manufacturers have had to adopt more flexible working processes – for example by examining plant-model mix, optimal shift patterns – so that they can adjust to larger-than-normal order volume swings.

- Investment strategies re-appraised, particularly in the areas of advanced technologies competing for capital.

- E-mobility given added momentum, for both OEMs and suppliers.

- Inventory planning. More volatility in final markets has created a need to manage flows of vehicles and aftermarket parts more carefully for final distribution channels.

Demand-side/retail impacts and responses

- Market forecasts have had to be revised quickly as demand conditions and regulations changed, often at very short notice. Agility and speed of response is key, with the right tools and analytical frameworks in place.

- Lessons have been learnt in cash management and making credit lines available quickly as needed.

- OEMs have had to work with distribution groups and dealers on new protocols and processes for customer interface – both on-site and on-line. The pandemic forced some to a greater level of cooperation and collaboration than was previously the case.

- Online marketing and retail given a boost. The role of the dealer and dealer-manufacturer relationships, interfaces with the customer, are all in the process of being reset.

- Growth of online retail has created greater demand for LCVs involved in goods distribution to consumers. Electric LCVs will likely be a strong growth pole for urban distribution needs.

- Private mobility – and car ownership – is potentially more attractive as modal choices for journeys as working patterns (less daily commuting) change. Micro-mobility in urban areas is a dynamic field with new disruptors allied to emerging technologies, as illustrated by the growth of electric scooters. Sustainability (and air quality) considerations from transport authorities are playing an increasing role in regulatory frameworks that underpin modal mix trends.